King Baby Bracelet Day of the Dead Skull

| Twenty-four hours of the Dead | |

|---|---|

Día de Muertos altar commemorating a deceased man in Milpa Alta, Mexico City | |

| Observed by | United mexican states, and regions with large Mexican populations |

| Type |

|

| Significance | Prayer and remembrance of friends and family members who take died |

| Celebrations | Creation of home altars to remember the dead, traditional dishes for the 24-hour interval of the Expressionless |

| Begins | November 1 |

| Ends | November 2 |

| Date | November ii |

| Next time | two November 2022 (2022-11-02) |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | All Saints' 24-hour interval, All Hallow'south Eve, All Souls Day[ane] |

The Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos or Día de los Muertos)[2] [3] is a vacation traditionally celebrated on Nov 1 and ii, though other days, such every bit October 31 or November half dozen, may be included depending on the locality.[four] [five] [six] It largely originated in Mexico,[1] where it is mostly observed, only too in other places, peculiarly by people of Mexican heritage elsewhere. Although associated with the Western Christian Allhallowtide observances of All Hallow'southward Eve, All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day,[1] it has a much less solemn tone and is portrayed every bit a vacation of joyful celebration rather than mourning.[7] The multi-twenty-four hours holiday involves family and friends gathering to pay respects and to remember friends and family unit members who take died. These celebrations tin can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.[8]

Traditions connected with the holiday include honoring the deceased using calaveras and aztec marigold flowers known as cempazúchitl, edifice home altars called ofrendas with the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these items every bit gifts for the deceased.[9] The celebration is not solely focused on the dead, as information technology is too common to give gifts to friends such every bit candy sugar skulls, to share traditional pan de muerto with family and friends, and to write low-cal-hearted and frequently irreverent verses in the form of mock epitaphs dedicated to living friends and acquaintances, a literary form known as calaveras literarias.[10]

In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[11]

Origins, History, and similarities to other festivities

Mexican academics are divided on whether the festivity has indigenous pre-Hispanic roots or whether it is a 20th-century rebranded version of a Spanish tradition developed by the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas to encourage Mexican nationalism through an "Aztec" identity.[12] [13] [14] The festivity has become a national symbol and as such is taught in the nation'due south school system, typically asserting a native origin.[15] In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative Listing of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[xi]

Views differ on whether the festivity has indigenous pre-Hispanic roots, whether it is a more modern accommodation of an existing European tradition, or a combination of both equally a manifestation of syncretism. Similar traditions tin be traced back to Medieval Europe, where celebrations like All Saints' Mean solar day and All Souls' 24-hour interval are observed on the same days in places similar Spain and Southern Europe. Critics of the native American origin claim that even though pre-Columbian United mexican states had traditions that honored the dead, current depictions of the festivity accept more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the imperceptible nature of life.[xvi] [12] Over the past decades, however, Mexican academia has increasingly questioned the validity of this assumption, even going as far equally calling information technology a politically motivated fabrication. Historian Elsa Malvido, researcher for the Mexican INAH and founder of the establish's Taller de Estudios sobre la Muerte, was the offset to exercise so in the context of her wider research into Mexican attitudes to decease and disease beyond the centuries. Malvido completely discards a native or fifty-fifty syncretic origin arguing that the tradition tin be fully traced to Medieval Europe. She highlights the being of similar traditions on the same day, not only in Spain, but in the residue of Catholic Southern Europe and Latin America such as altars for the dead, sweets in the shape of skulls and bread in the shape of bones.[xvi]

Agustin Sanchez Gonzalez has a similar view in his article published in the INAH's bi-monthly periodical Arqueología Mexicana. Gonzalez states that, even though the "indigenous" narrative became hegemonic, the spirit of the festivity has far more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and expiry personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life. He too highlights that in the 19th century press there was little mention of the Day of the Expressionless in the sense that we know information technology today. All there was were long processions to cemeteries, sometimes ending with drunkenness. Elsa Malvido, besides points to the recent origin of the tradition of "velar" or staying up all night with the dead. Information technology resulted from the Reform Laws nether the presidency of Benito Juarez which forced family unit pantheons out of Churches and into civil cemeteries, requiring rich families having servants guarding family possessions displayed at altars.[16]

The historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort has farther demonstrated how the credo known as indigenismo became more and more closely linked to mail-revolutionary official projects whereas Hispanismo was identified with conservative political stances. This sectional nationalism began to readapt all other cultural perspectives to the point that in the 1930s, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was officially promoted by the authorities as a substitute for the Spanish Three Kings tradition, with a person dressed upward as the deity offer gifts to poor children.[12]

In this context, the Day of the Dead began to be officially isolated from the Catholic Church by the leftist regime of Lázaro Cárdenas motivated both by "indigenismo" and left-leaning anti-clericalism. Malvido herself goes as far as calling the festivity a "Cardenist invention" whereby the Catholic elements are removed and accent is laid on ethnic iconography, the focus on expiry and what Malvido considers to be the cultural invention according to which Mexicans venerate decease.[xiv] [17] Gonzalez explains that Mexican nationalism adult diverse cultural expressions with a seal of tradition but which are essentially social constructs which eventually developed ancestral tones. One of these would exist the Catholic Día de Muertos which, during the 20th century, appropriated the elements of an ancient heathen rite.[12]

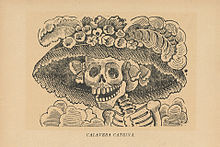

One key element of the re-adult festivity which appears during this fourth dimension is La Calavera Catrina by Mexican lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. According to Gonzalez, whereas Posada is portrayed in electric current times as the "restorer" of Mexico'southward pre-Hispanic tradition he was never interested in Native American civilization or history. Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary images which are far closer to those of the European renaissance or the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish state of war of Independence against Napoleon than the Mexica tzompantli. The contempo trans-atlantic connection tin can besides be observed in the pervasive employ of couplet in allegories of decease and the play Don Juan Tenorio by 19th Spanish writer José Zorrilla which is represented on this date both in Kingdom of spain and in United mexican states since the early on 19th century due to its ghostly apparitions and cemetery scenes.[12]

Opposing views assert that despite the obvious European influence, at that place exists proof of pre-Columbian festivities that were very similar in spirit, with the Aztec people having at least six celebrations during the year that were very like to Day of the Dead, the closest ane being Quecholli, a celebration that honored Mixcóatl (the god of war) and was historic between October 20 and November 8. This celebration included elements such equally the placement of altars with food (tamales) nigh the burying grounds of warriors to help them in their journey to the afterlife.[13] Influential Mexican poet and Nobel prize laureate Octavio Paz strongly supported the syncretic view of the Día de Muertos tradition being a continuity of ancient Aztec festivals jubilant death, as is well-nigh evident in the chapter "All Saints, 24-hour interval of the Dead" of his 1950 volume-length essay The Labyrinth of Solitude.[xviii]

Regardless of its origin, the festivity has become a national symbol in Mexico and as such is taught in the nation's schoolhouse organization, typically asserting a native origin. It is also a school holiday nationwide.[xv]

Observance in Mexico

Altars ( ofrendas )

During Día de Muertos, the tradition is to build private altars ("ofrendas") containing the favorite foods and beverages, too as photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, and so the souls will hear the prayers and the words of the living directed to them. These altars are ofttimes placed at abode or in public spaces such equally schools and libraries, merely information technology is also common for people to go to cemeteries to place these altars next to the tombs of the departed.[eight]

Mexican cempasúchil (marigold) is the traditional flower used to honor the dead.

Plans for the day are made throughout the year, including gathering the appurtenances to be offered to the dead. During the three-twenty-four hour period period families unremarkably clean and decorate graves;[nineteen] most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas (altars), which oft include orange Mexican marigolds (Tagetes erecta) chosen cempasúchil (originally named cempōhualxōchitl , Nāhuatl for '20 flowers'). In modernistic Mexico the marigold is sometimes called Flor de Muerto ('Blossom of Dead'). These flowers are idea to attract souls of the dead to the offerings. It is likewise believed the brilliant petals with a potent odour tin guide the souls from cemeteries to their family homes.[20] [21]

Toys are brought for dead children ( los angelitos , or 'the little angels'), and bottles of tequila, mezcal or pulque or jars of atole for adults. Families will too offer trinkets or the deceased's favorite candies on the grave. Some families take ofrendas in homes, ordinarily with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto ('staff of life of dead'), and saccharide skulls; and beverages such every bit atole . The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.[19] [21] Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the "spiritual essence" of the ofrendas ' food, so though the celebrators eat the food afterward the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so the deceased can residue later their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such every bit the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all nighttime beside the graves of their relatives. In many places, people have picnics at the grave site, as well.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes;[19] these sometimes characteristic a Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blest Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other people, scores of candles, and an ofrenda . Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar, praying and telling anecdotes near the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing, so when they trip the light fantastic, the noise volition wake upward the dead; some will also dress up equally the deceased.

Nutrient

During 24-hour interval of the Dead festivities, nutrient is both eaten by living people and given to the spirits of their departed ancestors as ofrendas ('offerings').[22] Tamales are one of the about common dishes prepared for this day for both purposes.[23]

Pan de muerto and calaveras are associated specifically with Day of the Expressionless. Pan de muerto is a type of sweet gyre shaped similar a bun, topped with sugar, and often decorated with bone-shaped pieces of the same pastry.[24] Calaveras , or sugar skulls, display colorful designs to represent the vitality and individual personality of the departed.[23]

In addition to food, drinks are also important to the tradition of Solar day of the Dead. Historically, the main alcoholic drink was pulque while today families volition commonly drink the favorite beverage of their deceased ancestors.[23] Other drinks associated with the holiday are atole and champurrado , warm, thick, non-alcoholic masa drinks.

Agua de Jamaica (water of hibiscus) is a popular herbal tea made of the flowers and leaves of the Jamaican hibiscus plant (Hibiscus sabdariffa), known as flor de Jamaica in Mexico. It is served cold and quite sweet with a lot of ice. The ruby-cherry-red potable is also known as hibiscus tea in English-speaking countries.[25]

In the Yucatán Peninsula, mukbil pollo (píib chicken) is traditionally prepared on October 31 or November 1, and eaten by the family unit throughout the following days. It is similar to a big tamale, composed of masa and pork lard, and stuffed with pork, chicken, tomato, garlic, peppers, onions, epazote, achiote, and spices. Once stuffed, the mukbil pollo is bathed in kool sauce, made with meat goop, habanero chili, and corn masa. It is then covered in banana leaves and steamed in an underground oven over the course of several hours. Once cooked, it is dug up and opened to eat.[26] [27]

Calaveras

A mutual symbol of the vacation is the skull (in Spanish calavera ), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for skeleton), and foods such as chocolate or sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the proper noun of the recipient on the forehead. Saccharide skulls tin can be given equally gifts to both the living and the expressionless.[28] Other holiday foods include pan de muerto , a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls, often decorated with white frosting to look similar twisted bones.[21]

Calaverita

In some parts of the country, specially the larger cities, children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people's doors for a calaverita , a pocket-sized gift of candies or money; they also enquire passersby for it. This custom is similar to that of Halloween'due south trick-or-treating in the Us, but without the component of mischief to homeowners if no care for is given.[29]

Calaveras literarias

A distinctive literary form exists inside this vacation where people write short poems in traditional rhyming poesy, chosen calaveras literarias (lit. "literary skulls"), which are mocking, light-hearted epitaphs mostly defended to friends, classmates, co-workers, or family unit members (living or dead) just also to public or historical figures, describing interesting habits and attitudes, equally well as comedic or absurd anecdotes that use decease-related imagery which includes but is non express to cemeteries, skulls, or the grim reaper, all of this in situations where the dedicatee has an encounter with death itself.[30] This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century later on a paper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future which included the words "and all of us were dead", and and so proceeding to read the tombstones. Electric current newspapers dedicate calaveras literarias to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the way of the famous calaveras of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator.[28] In modernistic Mexico, calaveras literarias are a staple of the holiday in many institutions and organizations, for example, in public schools, students are encouraged or required to write them equally function of the language class.[10]

Posada created what might be his most famous print, he called the impress La Calavera Catrina ("The Elegant Skull") every bit a parody of a Mexican upper-grade female. Posada's intent with the epitome was to ridicule the others that would claim the civilisation of the Europeans over the culture of the indigenous people. The image was a skeleton with a large floppy lid busy with 2 big feathers and multiple flowers on the acme of the chapeau. Posada's striking epitome of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Twenty-four hours of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.[28]

Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this solar day.

Local traditions

The traditions and activities that have identify in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal, often varying from town to boondocks. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, the tradition is very different if the deceased is a kid rather than an adult. On Nov ane of the yr after a child's expiry, the godparents set a tabular array in the parents' home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto , a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them), and candles. This is meant to gloat the kid'due south life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, ofttimes with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the boondocks. At midnight on November ii, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the eye of the lake where there is a cemetery, to award and gloat the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the Country of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in commutation for veladoras (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased. In render the visitors receive tamales and atole . This is washed but past the owners of the business firm where someone in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas go far early to consume for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set upward to receive the visitors.

Another peculiar tradition involving children is La Danza de los Viejitos (the Dance of the Former Men) where boys and young men dressed similar grandfathers crouch and jump in an energetic dance.[31]

In the 2015 James Bail film Spectre, the opening sequence features a Twenty-four hours of the Dead parade in Mexico Metropolis. At the time, no such parade took place in Mexico Urban center; 1 year later, due to the interest in the moving-picture show and the government want to promote the Mexican culture, the federal and local government decided to organize an bodily Día de Muertos parade through Paseo de la Reforma and Centro Historico on Oct 29, 2016, which was attended by 250,000 people.[32] [33] [34] This could be seen every bit an example of the pizza effect. The idea of a massive celebration was besides popularized in the Disney Pixar film Coco.

Observances outside of Mexico

America

United States

Women with calaveras makeup celebrating Día de Muertos in the Mission District of San Francisco, California

In many U.S. communities with Mexican residents, Twenty-four hours of the Dead celebrations are very like to those held in Mexico. In some of these communities, in states such equally Texas,[35] New Mexico,[36] and Arizona,[37] the celebrations tend to be mostly traditional. The All Souls Procession has been an annual Tucson, Arizona, outcome since 1990. The effect combines elements of traditional Day of the Dead celebrations with those of pagan harvest festivals. People wearing masks carry signs honoring the dead and an urn in which people tin place slips of paper with prayers on them to be burned.[38] As well, One-time Town San Diego, California, annually hosts a traditional two-twenty-four hours commemoration culminating in a candlelight procession to the historic El Campo Santo Cemetery.[39]

The festival as well is held annually at historic Woods Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Obviously neighborhood. Sponsored by Forest Hills Educational Trust and the folkloric functioning group La Piñata, the Day of the Expressionless festivities gloat the cycle of life and death. People bring offerings of flowers, photos, mementos, and food for their departed loved ones, which they identify at an elaborately and colorfully decorated altar. A plan of traditional music and dance likewise accompanies the community event.

The Smithsonian Establishment, in collaboration with the University of Texas at El Paso and Second Life, have created a Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum and accompanying multimedia due east-volume: Día de los Muertos: Day of the Dead. The projection'south website contains some of the text and images which explain the origins of some of the customary core practices related to the Day of the Dead, such as the background behavior and the offrenda (the special chantry commemorating ane's deceased loved one).[40] The Made For iTunes multimedia east-volume version provides additional content, such every bit farther details; additional photo galleries; popular-up profiles of influential Latino artists and cultural figures over the decades; and video clips[41] of interviews with artists who brand Día de Muertos-themed artwork, explanations and performances of Aztec and other traditional dances, an animation brusk that explains the customs to children, virtual poetry readings in English language and Spanish.[42] [43]

In 2021, the Biden-Harris administration celebrated the Día de Muertos.[44]

California

Santa Ana, California, is said to concord the "largest outcome in Southern California" honoring Día de Muertos, called the annual Noche de Altares , which began in 2002.[45] The celebration of the Day of the Dead in Santa Ana has grown to two large events with the creation of an event held at the Santa Ana Regional Transportation Center for the kickoff fourth dimension on November 1, 2015.[46]

In other communities, interactions between Mexican traditions and American culture are resulting in celebrations in which Mexican traditions are being extended to make artistic or sometimes political statements. For example, in Los Angeles, California, the Self Help Graphics & Art Mexican-American cultural center presents an almanac Day of the Expressionless celebration that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to laurels the victims of the Republic of iraq War, highlighting the high casualty charge per unit among Latino soldiers. An updated, intercultural version of the Day of the Dead is also evolving at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.[47] There, in a mixture of Native Californian fine art, Mexican traditions and Hollywood hip, conventional altars are set up adjacent with altars to Jayne Mansfield and Johnny Ramone. Colorful native dancers and music intermix with performance artists, while sly pranksters play on traditional themes.

Similar traditional and intercultural updating of Mexican celebrations are held in San Francisco. For example, the Galería de la Raza, SomArts Cultural Middle, Mission Cultural Center, de Young Museum and altars at Garfield Square by the Marigold Project.[48] Oakland is home to Corazon Del Pueblo in the Fruitvale district. Corazon Del Pueblo has a store offering handcrafted Mexican gifts and a museum devoted to Mean solar day of the Dead artifacts. Too, the Fruitvale district in Oakland serves as the hub of the Día de Muertos annual festival which occurs the concluding weekend of Oct. Here, a mix of several Mexican traditions come together with traditional Aztec dancers, regional Mexican music, and other Mexican artisans to celebrate the day.[49]

Asia and Oceania

Mexican-style Mean solar day of the Dead celebrations occur in major cities in Australia, Republic of the fiji islands, and Republic of indonesia. Additionally, prominent celebrations are held in Wellington, New Zealand, consummate with altars celebrating the deceased with flowers and gifts.[fifty] In the Philippines "Undás", "Araw ng mga Yumao" (Tagalog: "Day of those who have died"), coincides with the Roman Cosmic's celebration of All Saints' Day and continues on to the post-obit twenty-four hour period: All Souls' Day. Filipinos traditionally observe this day past visiting the family dead to clean and repair their tombs. Offerings of prayers, flowers, candles,[51] and even food, while Chinese Filipinos additionally burn down joss sticks and joss newspaper (kim). Many besides spend the day and ensuing night holding reunions at the cemetery, having feasts and merriment.

Europe

As part of a promotion by the Mexican diplomatic mission in Prague, Czech Republic, since the late 20th century, some local citizens join in a Mexican-style Day of the Dead. A theater group conducts events involving candles, masks, and make-up using luminous paint in the form of carbohydrate skulls.[52] [53]

Americas

Belize

In Belize, Day of the Dead is practiced by people of the Yucatec Maya ethnicity. The commemoration is known as Hanal Pixan which means 'food for the souls' in their linguistic communication. Altars are synthetic and decorated with food, drinks, candies, and candles put on them.

Bolivia

Día de las Ñatitas ("Twenty-four hours of the Skulls") is a festival historic in La Paz, Republic of bolivia, on May 5. In pre-Columbian times indigenous Andeans had a tradition of sharing a day with the bones of their ancestors on the third yr after burial. Today families go on only the skulls for such rituals. Traditionally, the skulls of family unit members are kept at home to watch over the family and protect them during the twelvemonth. On November 9, the family crowns the skulls with fresh flowers, sometimes also dressing them in various garments, and making offerings of cigarettes, coca leaves, alcohol, and various other items in thanks for the year's protection. The skulls are also sometimes taken to the cardinal cemetery in La Paz for a special Mass and blessing.[54] [55] [56]

Brazil

The Brazilian public holiday of Dia de Finados, Dia dos Mortos or Dia dos Fiéis Defuntos (Portuguese: "24-hour interval of the Dead" or "Day of the True-blue Deceased") is celebrated on Nov 2. Similar to other 24-hour interval of the Expressionless celebrations, people go to cemeteries and churches with flowers and candles and offer prayers. The celebration is intended as a positive honoring of the dead. Memorializing the dead draws from indigenous and European Catholic origins.

Republic of costa rica

Costa Rica celebrates Día De Los Muertos on November two. The mean solar day is as well chosen Día de Todos Santos (All Saints Twenty-four hours) and Día de Todos Almas (All Souls Solar day). Cosmic masses are celebrated and people visit their loved ones' graves to decorate them with flowers and candles.[57]

Ecuador

In Ecuador the Day of the Dead is observed to some extent by all parts of society, though it is especially important to the indigenous Kichwa peoples, who make upward an estimated quarter of the population. Indigena families gather together in the community cemetery with offerings of nutrient for a day-long remembrance of their ancestors and lost loved ones. Ceremonial foods include colada morada, a spiced fruit porridge that derives its deep purple color from the Andean blackberry and purple maize. This is typically consumed with wawa de pan, a breadstuff shaped like a swaddled infant, though variations include many pigs—the latter being traditional to the city of Loja. The bread, which is wheat flour-based today, only was made with masa in the pre-Columbian era, can be made savory with cheese inside or sugariness with a filling of guava paste. These traditions have permeated mainstream society, besides, where nutrient establishments add together both colada morada and gaugua de pan to their menus for the flavor. Many non-ethnic Ecuadorians visit the graves of the deceased, cleaning and bringing flowers, or preparing the traditional foods, also.[58]

Guatemala

Guatemalan celebrations of the Day of the Dead, on November 1, are highlighted by the construction and flying of giant kites.[59] Information technology is customary to fly kites to help the spirits find their way back to Earth. A few kites take notes for the dead attached to the strings of the kites. The kites are used every bit a kind of telecommunication to heaven.[28] A big event also is the consumption of fiambre, which is made only for this day during the year.[28] In addition to the traditional visits to grave sites of ancestors, the tombs and graves are decorated with flowers, candles, and food for the expressionless. In a few towns, Guatemalans repair and repaint the cemetery with vibrant colors to bring the cemetery to life. They fix things that have gotten damaged over the years or simply only need a bear on-upwards, such as wooden grave cross markers. They also lay flower wreaths on the graves. Some families accept picnics in the cemetery.[28]

Peru

Unremarkably people visit the cemetery and bring flowers to decorate the graves of expressionless relatives. Sometimes people play music at the cemetery.[60]

Europe

Southern Italia and Sicily

A traditional biscotti-type cookie, ossa di morto or bones of the expressionless are made and placed in shoes in one case worn by dead relatives.[61]

See also

- Danse Macabre

- Literary Calaverita

- Samhain

- Santa Muerte

- Skull art

- Thursday of the Expressionless

- Veneration of the dead

- Walpurgis Night

References

- ^ a b c d Foxcroft, Nigel H. (Oct 28, 2019). The Kaleidoscopic Vision of Malcolm Lowry: Souls and Shamans. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN978-one-4985-1658-7.

However, owing to the subjugation of the Aztec Empire by the Spanish conqueror, Hernan Coretes in 1519–1521, this festival increasingly fell under Hispanic influence. It was moved from the beginning of summertime to late October—and and so to early Nov—and so that information technology would conicide with the Western Christian triduum (or three-twenty-four hours religious observance) of Allhallowtide (Hallowtide, Allsaintide, or Hallowmas). It lasts from October 31 to November 2 and comprises All Saint'southward Eve (Halloween), All Saints' Twenty-four hour period (All Hallows'), and All Souls' Day.

- ^ "Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos y Día de (los) Muertos (México) se escriben con mayúscula inicial" [Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos and Día de (los) Muertos (Mexico) are written with initial majuscule letter] (in Spanish). Fundéu. October 29, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ "¿'Día de Muertos' o 'Día de los Muertos'? El nombre usado en México para denominar a la fiesta tradicional en la que se honra a los muertos es 'Día de Muertos', aunque la denominación 'Día de los Muertos' también es gramaticalmente correcta" ['Día de Muertos' or 'Día de los Muertos'? The name used in Mexico to denominate the traditional commemoration in which death is honored is 'Día de Muertos', although the denomination 'Día de los Muertos' is also grammatically correct] (in Castilian). Royal Spanish University Official Twitter Account. November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Sacred Places of a Lifetime. National Geographic. 2008. p. 273. ISBN978-1-4262-0336-seven.

Twenty-four hours of the Expressionless celebrations take place over October 31 ... Nov one (All Saints' Mean solar day), and November 2.

- ^ Skibo, James; Skibo, James Grand.; Feinman, Gary (Jan 14, 1999). Pottery and People. University of Utah Press. p. 65. ISBN978-0-87480-577-2.

In Yucatan, however, the Day of the Expressionless rituals occur on Oct 31, Nov ane, and Nov vi.

- ^ Arnold, Dean E. (February 7, 2018). Maya Potters' Indigenous Noesis: Cognition, Engagement, and Practice. Academy Printing of Colorado. p. 206. ISBN978-1-60732-656-4.

pottery equally a distilled taskscape is best illustrated in the pottery required for Mean solar day of the Dead rituals (on October 31, Nov i, and November vi), when the spirits of deceased ancestors come back to the land of the living.

- ^ Club, National Geographic (October 17, 2012). "Dia de los Muertos". National Geographic Gild . Retrieved April viii, 2019.

- ^ a b Palfrey, Dale Hoyt (1995). "The Day of the Dead". Día de los Muertos Index. Admission Mexico Connect. Archived from the original on November thirty, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ "Dia de los Muertos". National Geographic Gild. Oct 17, 2012. Archived from the original on November two, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Chávez, Xóchitl (October 23, 2018). "Literary Calaveras". Smithsonian Voices.

- ^ a b "Indigenous festivity dedicated to the dead". UNESCO. Archived from the original on Oct xi, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Día de muertos, ¿tradición prehispánica o invención del siglo XX?". Relatos e Historias en México. November 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Dos historiadoras encuentran diverso origen del Día de Muertos en México". www.opinion.com.bo.

- ^ a b ""Día de Muertos, un invento cardenista", decía Elsa Malvido". El Universal. November 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "El Día de Muertos mexicano nació como arma política o tradición prehispánica - Arte y Cultura - IntraMed". world wide web.intramed.internet.

- ^ a b c "Orígenes profundamente católicos y no prehispánicos, la fiesta de día de muertos". www.inah.gob.mx.

- ^ "09an1esp". www.jornada.com.mx.

- ^ Paz,Octavio. 'The Labyrinth of Solitude'. Northward.Y.: Grove Press, 1961.

- ^ a b c Salvador, R.J. (2003). John D. Morgan and Pittu Laungani (ed.). Death and Bereavement Around the World: Death and Bereavement in the Americas. Death, Value and Pregnant Series, Vol. 2. Amityville, New York: Baywood Publishing Company. pp. 75–76. ISBN978-0-89503-232-4.

- ^ "5 Facts About Día de los Muertos (The Twenty-four hour period of the Dead)". Smithsonian Insider. October 30, 2016. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Brandes, Stanley (1997). "Carbohydrate, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of United mexican states'south Day of the Dead". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (2): 275. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179316.

- ^ Turim, Gayle (November 2, 2012). "Day of the Dead Sweets and Treats". History Stories. History Aqueduct. Archived from the original on June half-dozen, 2015. Retrieved July ane, 2015.

- ^ a b c Godoy, Maria (Nov 2016). "Saccharide Skulls, Tamales And More: Why Is That Nutrient On The Solar day Of The Expressionless Altar?". NPR. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Castella, Krystina (October 2010). "Pan de Muerto Recipe". Epicurious. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ "Jamaica iced tea". Cooking in Mexico. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Kennedy, D. (2018). Cocina esencial de México. Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 156. ISBN9786071656636 . Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ R., Muñoz. "Muc bil pollo". Diccionario enciclopédico de la Gastronomía Mexicana [Enciclopedic lexicon of Mexican Gastronomy] (in Castilian). Larousse Cocina.

- ^ a b c d e f Marchi, Regina M (2009). Twenty-four hour period of the Dead in the United states : The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Printing. p. 17. ISBN978-0-8135-4557-8.

- ^ "Mi Calaverita: Mexico's Trick or Treat". Mexperience. October 31, 2020.

- ^ "These wicked Mean solar day of the Dead poems don't spare anyone". PBS NewsHour. November ii, 2018. Retrieved May six, 2019.

- ^ "Día de los Muertos or Twenty-four hour period of the Dead". Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved Baronial 29, 2018.

- ^ "Mexico City stages start Twenty-four hours of the Dead parade". BBC. October 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Fotogalería: Desfile por Día de Muertos reúne a 250 mil personas". Excélsior (in Spanish). October 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved November one, 2016.

- ^ "Galerías Archivo". Televisa News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November one, 2016.

- ^ Wise, Danno. "Port Isabel's Day of the Expressionless Commemoration". Texas Travel. Almost.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ "Dia de los Muertos". visitalbuquerque.org. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Hedding, Judy. "Day of the Dead". Phoenix. Well-nigh.com. Archived from the original on December eleven, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ White, Erin (November five, 2006). "All Souls Procession". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved Nov 28, 2007.

- ^ "Old Town San Diego's Dia de los Muertos". Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum. Día de los Muertos: Day of the Dead (Version one.ii ed.). Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved Oct 31, 2014.

- ^ "Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum". Ustream. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum. "Day of the Dead". Theater of the Expressionless. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved Oct 31, 2014.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution. "Smithsonian-UTEP Día de los Muertos Festival: A 2d and 3D Experience!". Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum Press Release. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009.

- ^ @LaCasaBlanca (November i, 2021). "Feliz Día de los Muertos de la Administración Biden-Harris. Hoy y mañana, el Presidente y la Primera Dama reconocerán el Día de los Muertos con la primera ofrenda ubicada en la Casa Blanca" (Tweet) (in Spanish). Retrieved November 4, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Less-scary holiday: Some faith groups offer alternatives to Halloween fox-or-treating". The Orange County Annals. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Viva la Vida or Noche de Altares? Santa Ana'southward downtown partitioning fuels dueling Day of the Dead events". The Orange County Register. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Quinones, Sam (October 28, 2006). "Making a night of 24-hour interval of the Dead". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ "Dia de los Muertos [Day of the Expressionless] – San Francisco". Archived from the original on Oct 17, 2014. Retrieved October xix, 2014.

- ^ Elliott, Vicky (October 27, 2000). "Lively Petaluma festival marks Mean solar day of the Dead". The San Francisco Relate. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved August half-dozen, 2010.

- ^ "Twenty-four hours of the Dead in Wellington, New Zealand". Scoop.co.nz. Oct 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ "All Saints Day effectually the world". Guardian Weekly. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on Oct 29, 2018. Retrieved Oct 30, 2018.

- ^ "48 Best Sugar Skull Makeup Creations To Day of the Dead". August 22, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Day of the Expressionless in Prague". Radio Czech. October 24, 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007.

- ^ Guidi, Ruxandra (Nov 9, 2007). "Las Natitas". BBC. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Fiona (November 8, 2005). "Bolivians Honor Skull-Toting Tradition". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February eighteen, 2008. Retrieved December xxx, 2007.

- ^ "All Saints day in Bolivia – "The skull festival"". Bolivia Line (May 2005). Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved December twenty, 2007.

- ^ Costa rica Celebrates The Twenty-four hour period of the Dead Outward Bound Costa Rica, 2012-eleven-01.

- ^ Ortiz, Gonzalo (October xxx, 2010). "Variety in Remembering the Expressionless". InterPress Service News Agency. Archived from the original on November four, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Burlingame, Betsy; Woods, Joshua. "Visit to cemetery in Guatemala". Expatexchange.com. Archived from the original on Oct 14, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ "Perú: así se vivió Día de todos los santos en cementerios de Lima". Peru. republic of peru.com. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on November seven, 2017. Retrieved October thirty, 2017.

- ^ "Bones of the Expressionless Cookies - Ossa Di Morto". Savoring Italian republic. October 24, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

Further reading

- Andrade, Mary J. Day of the Dead A Passion for Life – Día de los Muertos Pasión por la Vida. La Oferta Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9791624-04

- Anguiano, Mariana, et al. Las tradiciones de Día de Muertos en México. Mexico Urban center 1987.

- Brandes, Stanley (1997). "Sugar, Colonialism, and Decease: On the Origins of Mexico's Day of the Expressionless". Comparative Studies in Club and History. 39 (2): 270–99. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). "The Day of the Dead, Halloween, and the Quest for Mexican National Identity". Periodical of American Folklore. 111 (442): 359–80. doi:x.2307/541045. JSTOR 541045.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). "Iconography in Mexico'southward Day of the Dead". Ethnohistory. Knuckles University Press. 45 (2): 181–218. doi:10.2307/483058. JSTOR 483058.

- Brandes, Stanley (2006). Skulls to the Living, Breadstuff to the Dead. Blackwell Publishing. p. 232. ISBN978-1-4051-5247-one.

- Cadafalch, Antoni. The Day of the Dead. Korero Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1-907621-01-7

- Carmichael, Elizabeth; Sayer, Chloe. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Twenty-four hours of the Dead in United mexican states. Uk: The Bath Press, 1991. ISBN 0-7141-2503-2

- Conklin, Paul (2001). "Death Takes a Holiday". U.S. Cosmic. 66: 38–41.

- Garcia-Rivera, Alex (1997). "Death Takes a Holiday". U.South. Catholic. 62: 50.

- Haley, Shawn D.; Fukuda, Curt. Solar day of the Dead: When 2 Worlds Come across in Oaxaca. Berhahn Books, 2004. ISBN 1-84545-083-three

- Lane, Sarah and Marilyn Turkovich, Días de los Muertos/Days of the Dead. Chicago 1987.

- Lomnitz, Claudio. Death and the Thought of Mexico. Zone Books, 2005. ISBN 1-890951-53-6

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, et al. "Miccahuitl: El culto a la muerte," Special issue of Artes de México 145 (1971)

- Nutini, Hugo G. Todos Santos in Rural Tlaxcala: A Syncretic, Expressive, and Symbolic Analysis of the Cult of the Dead. Princeton 1988.

- Oliver Vega, Beatriz, et al. The Days of the Expressionless, a Mexican Tradition. Mexico Urban center 1988.

- Roy, Ann (1995). "A Crack Betwixt the Worlds". Democracy. 122: thirteen–xvi.

rouleauupellift67.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_of_the_Dead

0 Response to "King Baby Bracelet Day of the Dead Skull"

Post a Comment